Nairobi Law Monthly Published 30/06/2011

Chris Okemo spent a decade battling efforts to enact a law to fight money laundering; then he lost. As he contests attempts to extradite him and Samuel Gichuru to Jersey Island, we trace key events and how a global war on corporate bribery could ensnare bigger fish in Kenya

By Michael Rigby

On the afternoon of November 18, 1999, after a heated parliamentary session that debated female circumcision, broken toilets in Wundanyi Prison and police harassment of a tourist, Finance Minister Chris Okemo, the legislator from Nambale, finally got the chance to tackle the weighty matter before a Committee of the Whole House.

For a few years, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) Governor Micah Cheserem and technocrats at the Treasury had been fighting to keep the banking sector afloat after the near collapse of the National Bank of Kenya, the Kenya Commercial Bank and a host of small and mid-sized banks. They had staunched the wound, and were trying to push proposals that were intended to strengthen the balance sheets of these banks, and make it harder for owner-managers to loot depositors’ savings and investors’ capital through insider lending.

To achieve this, they proposed to limit the influence of owner-managers by imposing a maximum shareholding they could buy in one bank. They also wanted more transparency in the ownership structures of banks by lifting the veil on the impenetrable web of nominee companies used by crooked owners to clean up dirty money offshore.

These two issues were the real scourge that caused the banking crisis of the 1980s and late 1990s, and would facilitate Kenya’s biggest tax evasion and money laundering scandal at the Charterhouse Bank between 2004 and 2006.

That day, when Mr Okemo took the floor, he proceeded to introduce a raft of significant amendments to the Banking Act, through the Finance Bill — the law that gives the government authority to spend taxpayers’ money every year — that would defeat the objectives of his advisers at the Treasury and CBK.

Soon, what would have been a hasty approval of routine “deletions” and “insertion” of letters, words and clauses into the Finance Bill that drew little attention of the members, turned into a swordplay between Mr Okemo, MP Owino Achola and then North Mugirango legislator Henry Obwocha. Both were questioning the minister’s intentions, but Mr Okemo got his way.

The red alert

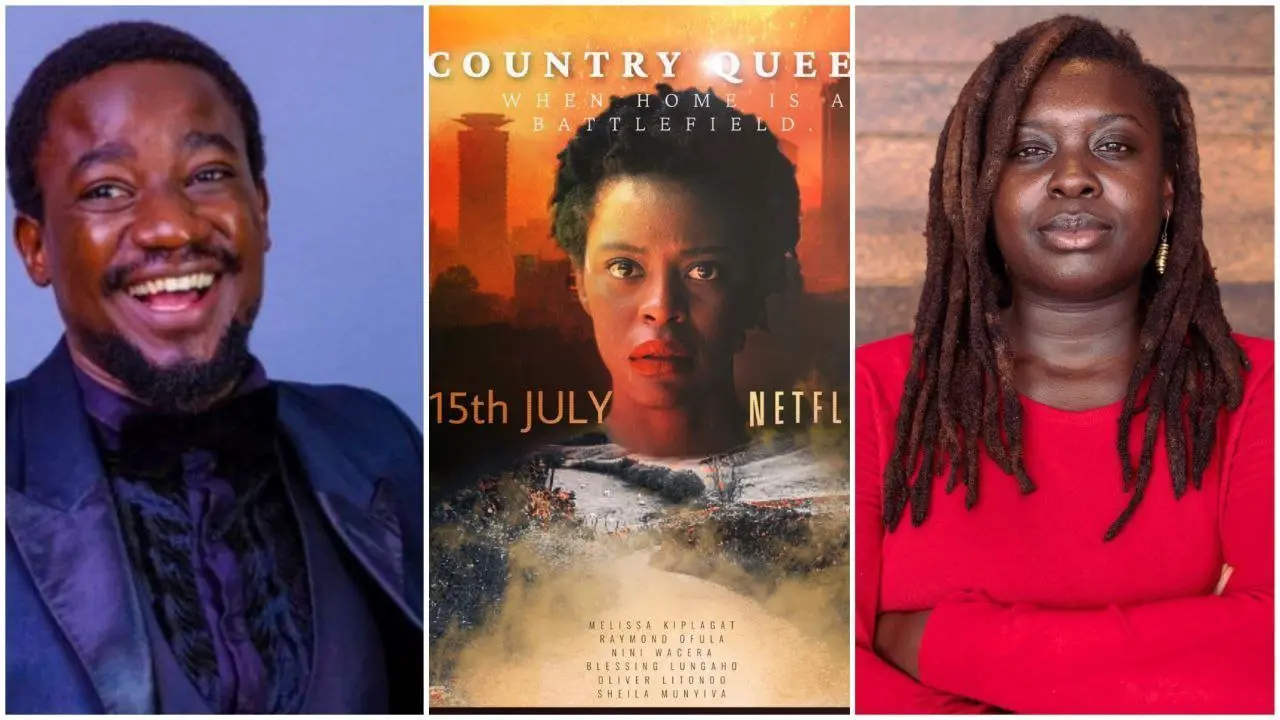

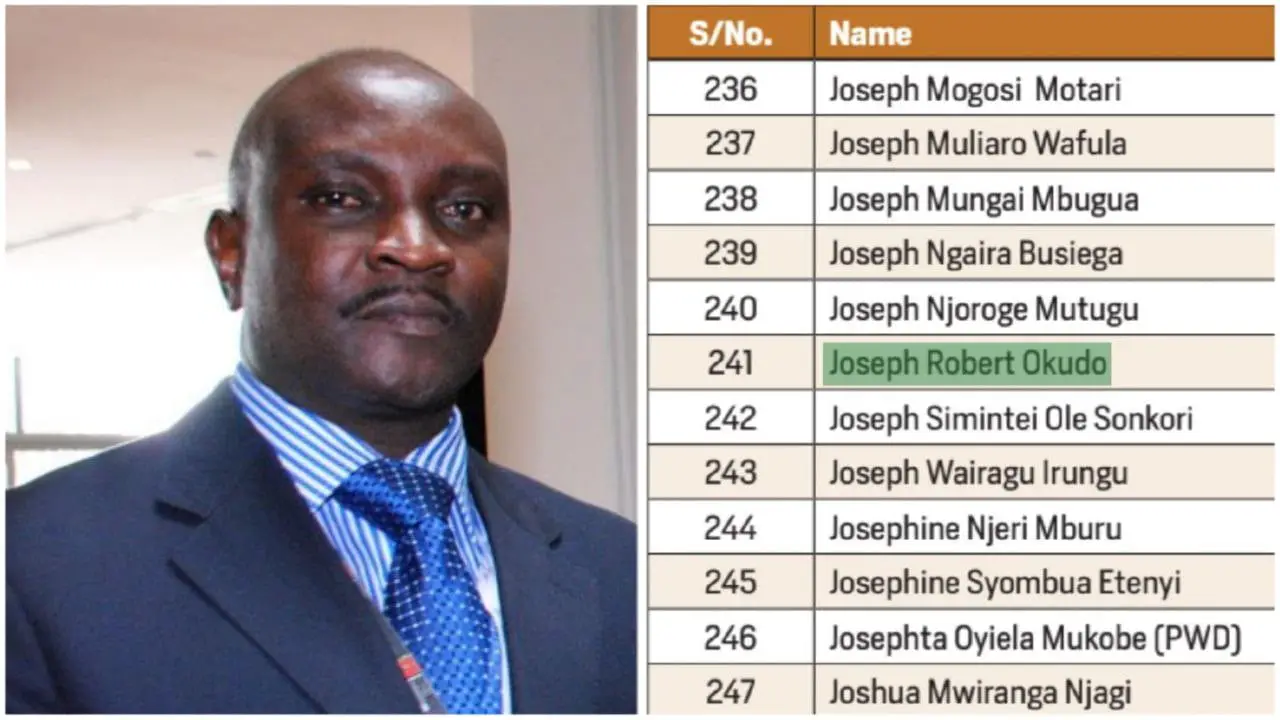

Last month, 12 years later, it now seems as if Mr Okemo had a canny sense of premonition in Parliament that day and on many other days over the last decade, as The Nairobi Law Monthly can now reveal, after Interpol issued an international warrant of arrest against him and former Managing Director of Kenya Power and lighting company (KPLC) Samuel Gichuru to face bribery and money-laundering charges in the British island of Jersey. KPLC is now known as Kenya Power.

The “red notice” was instigated by Jersey’s Attorney-General Timothy Le Cocq, who alleges that Mr Gichuru accepted bribes from foreign firms that contracted with KPLC between 1986 and 2002 and hid the money in the island. Some of these payments were allegedly made to Mr Okemo in his capacity as Finance minister and at another stage while he was Energy minister. Mr Okemo was Finance minister from 1999 to 2001 and Energy minister between 2001 and 2003. Mr Gichuru was managing director of KPLC between 1983 and 2003 when it was partially privatised.

“Both Gichuru and Okemo were public officers. The receipt of these bribes was not only greedy and dishonest but amounted to criminal offences,” said an arrest warrant issued by a Jersey court.

The duo face jail terms of 14 years if convicted. They face 53 charges relating to commissions paid by international companies, mostly between 1999 and 2002, totalling £4,459,572, Kr786,853 (Danish kroner) and US$3,207,360. The Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission (KACC) now wants to be part of the prosecution with the aim of disgorging any illegally acquired profits.

Locally, as Director of Public Prosecutions Keriako Tobiko prepares to seek extradition orders against the two in court, the case continues to cause reverberations among the Kenyan political and business elite. There are several important reasons for this. First, if a Kenyan court determines there is enough evidence for extradition, Mr Okemo and Mr Gichuru face a real chance of spending their sunset years fighting multi-jurisdictional court cases and possibly jail terms.

This could motivate them to work with the prosecution, which might not end up well for any accomplices. Second, under the reformed judicial system, the Office of Public Prosecution, KACC and the Kenya Revenue Authority will find themselves under parliamentary and public scrutiny if they fail to investigate and prosecute white-collar crimes aggressively.

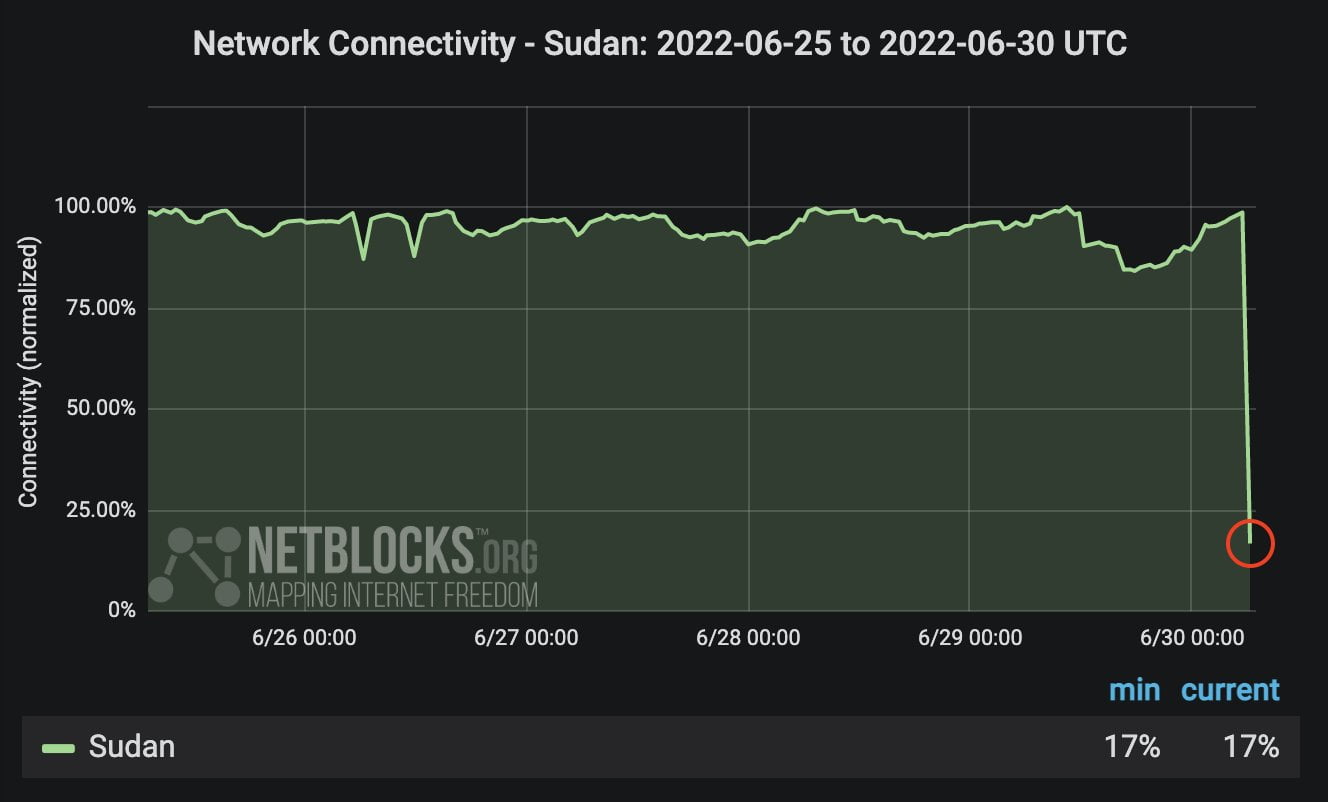

Third, while some may feel that Mr Gichuru and Mr Okemo seem to have been targeted, what is happening now has little to do with local politics. These two are victims of a systematic effort by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, led by the US and Britain, to scale up the foreign bribery war.

Prosecutorial sea change

The face behind this war is Mr Lanny Breuer, the Assistant Attorney-General for the Criminal Division of the US Department of Justice, who has been on the job since President Barack Obama came to power. Mr Breuer has been working closely with the Securities Exchange Commission and their tool is the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) of 1977.

After graduating from Columbia Law School, Mr Breuer was an Assistant District Attorney in Manhattan from 1985 to 1989. As a special White House counsel, he helped represent President Bill Clinton from 1997 to 1999 during independent-counsel and congressional investigations, and the impeachment hearings. On January 22, 2009, President Obama selected Mr Breuer to head the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice. He was confirmed by Senate on April 20, 2009 by a vote of 88-0.

According to data from Bloomberg Law Reports, 2010 was a landmark year in the enforcement of FCPA, which globally represented a sea change in the prosecution of international business bribery and 2011 is expected to be even better. According to Bloomberg, the US government resolved 50 FCPA cases, with 35 individuals awaiting trial. Cases against individuals have more than doubled since 2009. By 2010, the government collected more than $1 billion in corporate fines and disgorgements. This included the Alcatel case that touched on KenCell (now Airtel Kenya).

Globally, the US leads in gross prosecution numbers, accounting for more than 70 per cent of the cases filed, followed by UK at 4.3 per cent. Some of the companies netted included Siemens, which paid $448.5 million in criminal fines in 2009, of which $350 million was disgorged; KBR/Halliburton paid $402 million in 2009, of which $177 million was taken away; and BAE Systems, which paid $400 million in 2000 in a case that touched on Tanzania.

Big fish: KenCell and Safaricom

This war could soon claim even bigger fish going by a plea bargain and deferral agreement filed by the US Department of Justice in a Florida court in the case of US vs Alcatel-Lucent, SA, on December 27, 2010. Alcatel admitted to have bribed foreign officials in several countries, including Kenya and Nigeria, and paid $92 million in fines, $45 million of which was disgorged as illegal profits.

In Kenya, Alcatel confessed to have paid a $20 million bribe to executives of KenCell to secure a $87 million contract that would support the cell phone company’s network roll-out in 2000. It is suspected that this bribe was paid to facilitate the award of Kenya’s second mobile telephone company on January 28, 2000. KenCell was majority owned by businessman Naushad Merali, who continues to own a minority stake in Airtel Kenya. There is a possibility that either the Americans, French and Kenyans could be interested in pursuing this matter further to disgorge the illegal amounts and profits generated by this bribe.

This would also cast the spotlight on the shadowy Mobitelea, which at one point owned five per cent in Safaricom, Vodafone’s affiliate in Kenya.

According to reports in The Guardian, Mr Gavin Darby — Vodafone Group’s chief executive for the Americas, Africa, China and India — stated that Mobitelea was Vodafone’s chosen partner in Kenya and paid $5 million in cash and a five per cent stake in a company valued today at $2 billion “in return for its valued advice”. Documents obtained by The Guardian show Mobitelea was registered in Guernsey on June 18, 1999 — several months after Vodafone had struck a preliminary deal with the Kenyan government.

Mobitelea’s real owners are hidden behind two nominee firms, Guernsey-registered Mercator Nominees Ltd and Mercator Trustees Ltd. The directors are named as Anson Ltd and Cabot Ltd, based in Anguilla and Antigua. The British, in spite of their zeal to go after Mr Okemo and Mr Gichuru, have been seen to be reluctant to investigate a local firm and the matter has been in a lull.

Swordplay in the House

Unbeknown to the House, most of the deals that the Americans and the British are now pursuing aggressively were happening at the time Mr Okemo was blocking attempts to bring transparency in the ownership of banks and attempts to get CBK to share information in a global war on money laundering.

In that November 1999 debate on the Finance Bill, Mr Achola questioned Mr Okemo’s bid to delete a clause in the Banking Act that required financial institutions to name the actual beneficial shareholders of individuals hiding behind nominee accounts, and another one that limited the shareholding of families in a bank.

In a session chaired by Temporary Speaker Gitobu Imanyara, Mr Achola asked why a nominee has to indicate who is the actual owner of a specific share, “Why does he want that one to be stated?”

Mr Okemo in response said, “We are talking about associates and associates of associates. What we are saying is that, that is really carrying the relationship too far and it causes a constraint on ownership and entrepreneurship of the local people. What it means is that, if your wife is a shareholder in a bank, then her associate, could be a friend or a relative, cannot also be a shareholder in the same bank. So, I am thinking we have carried the definition of ownership too far. We have extended the relationship too limiting in terms of the shareholding. So, we are saying that, we end at the ownership and immediate relatives of the shareholder.”

In a follow-up question that would prove very illuminating in subsequent events in 2006 and 2011, Mr Achola asked: “Mr Temporary Deputy Chairman, Sir, I have no quarrel with that one which you have just deleted, my quarrel is with the next one, ‘(b)’. If you just read it that: ‘where any share is held by a company or by a nominee on behalf of another company, the company or the nominee as the case may be, shall disclose….’ What is the rationale, why do they need to?”

Mr Okemo answered, “Why would you have a nominee? You have a nominee because you would not want your own identity known. This is pure international banking practice. It is not unique to Kenya.”

The House approved what the minister wanted.

Then he proceed to petition for the deletion of Clause 86, and this immediately aroused the curiosity of Mr Obwocha, who observed, “This provision was very, very important…why does the minister want it deleted?”

Clause 86 read in part that: “Upon request made in the ordinary cause of business, the Central Bank may disclose any information referred to in subsection (2) to any monetary authority of financial regulatory authority within or outside Kenya where such information is reasonably required for the proper discharge of the functions of the requesting monetary authority or financial authority.”

In response, Mr Okemo said: “Sir, I am hiding nothing, I have a number of reasons. The first being that, right now, the exchange of information between monetary authorities is actually taking place… In the event of wanting to share information with other monetary authorities, there should be a reciprocal arrangement. For example, why should we divulge information to Uganda or Tanzania, if they are not having similar provisions in their Banking Act?

“I have checked and seen they do not exist. If there are special arrangements, for example, at the moment, there are initiatives for this anti-money laundering by the World Bank and a number of southern African countries. After the exercise is done and completed, there will be a protocol and that protocol will provide for reciprocity. At the moment, actually it is a superfluous requirement in the Banking Act.”

Mr Obwocha, who was not convinced by Mr Okemo’s explanation, argued for a proviso that accommodated the reciprocity rather than deleting an entire clause that would give Kenya room to refuse to cooperate with other countries investigating anti-money laundering crimes. Mr Matere Keriri presciently observed that Mr Okemo was trying to “deny himself the discretion of doing something, because this clause says, ‘may disclose’, which is not the same as saying, ‘You shall disclose’ to anybody.”

By robbing himself and CBK the discretion by deleting the clause, Mr Keriri observed that “it will mean that if the Minister happens to have friends whom he wishes to disclose the information to, he will have to come to Parliament to amend the Bill again. Why should he do that?”

With these deletions, Mr Okemo won the battle against the Treasury and CBK, introducing anti-money laundering through the backdoor — using the Central Bank Act and Finance Bill — nearly two years ahead of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, an event that galvanised Americans to launch a global campaign to fight money laundering which had been used as a conduit for terrorism finance.

It would take Kenya nearly a decade to pass a law aimed at fighting economic crimes, terrorism finance and money-laundering. And during this period, this legal vacuum provided a thriving environment for high-level corruption that greased the wheels of politics in the Kenyatta, Moi and Kibaki years.

Anti-money laundering filibuster

Nine years later, after intense pressure from the American government, which had given Kenya over $3 billion dollars for economic development and foreign military assistance, the then Finance Minister Amos Kimunya succeeded in putting the Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Bill on the agenda of the House. This is after three failed attempts in 2006, 2007, and 2008 that saw the Bills lapse before they were discussed due to the politics hanging around this law because it was wrongly considered to be targeting Muslims. This Bill had started its life under pressure from George W Bush’s government in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and was modelled on the International Money Laundering Abatement and Anti-Terrorism Finance Act of 2001, which was part of the dreaded Patriot Act in America. Kenya’s close association with America’s War on Terror sank hopes of enacting an anti-money laundering law.

However, on May 8, 2008, Mr Kimunya petitioned the House to move the Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Bill to the second reading. Dr Naomi Shaban seconded the Motion. Mr Okemo concurred and said that the Bill needs thorough scrutiny by the Departmental Committee on Finance, which he chaired. Though now supportive of this “piece of legislation that has been missing for dealing with the specific aspect of economic crimes”, Mr Okemo told Parliament that he had serious doubts about the motivations and the scope of the Bill.

“We know that money laundering takes place in this country,” he said. “The unfortunate thing is that most of the players in this kind of activity are usually the big boys, or the big fish. Therefore, we must make sure that the law is so tight that it can define clearly what money laundering is and how it can be traced and dealt with. My fear is that we should not open another avenue for corruption.

“In the process of tracing money launderers we should not create another group of corrupt people, who will use this avenue to harass people simply because they suspect that someone is involved in money laundering. Mr Speaker, Sir, the other concern that I would like to bring to the attention of the House is my worry that a lot of legislation somehow along the line is not homegrown. From my experience, when I was in the ministry (of Finance) before, some laws sometimes form part of the conditionalities by the World Bank and IMF to give us financial support.

“In a way, that is a form of blackmail. I believe that we should not accept that. We should pass this law because it is good for Kenya, and not because it is a condition for us to get money from financial institutions.”

The Charterhouse Bank ghost

On the afternoon of Thursday December 9, 2010, Mr Okemo — then the Chairman of the Departmental Committee on Finance, Planning and Trade — moved a Motion petitioning the House to adopt a report on Charterhouse Bank.

In this report, Mr Okemo and nine other legislators argued that Charterhouse, which had been closed four years earlier on allegations of massive tax evasion, money laundering and flouting Kenya’s banking laws, had been unfairly singled out and shabbily treated by CBK. They wanted this bank reopened immediately.

Charterhouse has been linked to Kilome MP Harun Mwau, who has been battling a cloud of allegations in Parliament, and more recently by the US government, over drug trafficking and money laundering. President Obama last month put him on a special watch list of notorious drug traffickers around the world.

On that Thursday afternoon, it was noted that the Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Uhuru Kenyatta was missing despite knowing the report tabled the previous day would be debated.

Every legislator who spoke supported the Motion and some could not help slam the then American Ambassador Michael E Ranneberger. According to the recommendation of the Finance Committee, there was no credible evidence that had been produced that Charterhouse had evaded taxes. On the question of money laundering, the bank could not be accused of having flouted laws that did not exist at the time.

While the bank was found to have repeatedly breached regulations that required banks to know their customers well and maintain proper documentation of transactions, which was established by a forensic investigation by PwC, this, according to the committee, was a minor infraction that should not have had the bank closed. The MPs reprimanded PwC for doing a shoddy job. And with that, Parliament shut the door to Kenya’s most controversial and massive tax evasion and money laundering investigation.

Fear in corporate boardrooms

According to experts on anti-corruption law, the gross prosecution numbers under the FCPA and UK Bribery Act are not worrying just because of the volume of the cases, but corporations are more concerned about emerging prosecutorial strategy that is being employed and which has led to success in the last three years.

According to T Markus Funk, a litigation partner and member of Perkin Coles’s Investigations and White Collar Defence Group, some of these strategies include:

· Governments are reaching deeper into the toolbox of traditional policing techniques such as undercover agents, informants, electronic surveillance and search warrants.

· Encouraging use of self-reporting mechanism, non-prosecution and deferral agreements like those used in the Alcatel case.

· Widening of whistle-blower bounty provisions to recruit an army of additional tipsters.

· The prosecution of individual defendants is now a priority as it is happening in the Gichuru and Okemo case.

· Specialisation of investigators in industry sectors.

· Attacking the demand side of crime and widening enforcement to catch bribe recipients and middlemen.

· In the US, the government will not award contracts to companies proved to have bribed foreign officials.

· Encouraging offenders to develop effective compliance and ethics programmes for employees and appointment of compliance officers.

· More countries are now working more closely in bribery investigations.

As foreign governments double their efforts to fight international business bribery, increased prosecution of individuals paying bribes and their recipients is one strategy likely to produce an effective outcome that could dramatically reduce high-level corruption in Africa. This strategy hits at both the demand and supply side of the problem.

Chronology-of-Gichuru-and-Okemo-Bribe

Download Okemo and Gichuru Arrest Warrants here

Arrest Warrant and Charge Sheet Samuel Gichuru and Chrysanthus Okemo April 2010 by Cyprian Nyakundi