This piece was written by Edward Luce for The Financial Times Limited.

‘Bring to the storehouse a full tenth of what you earn… I will open the windows of heaven for you and pour out all the blessings you need’ – Malachi 3:10

I met Dustin Rollo one evening in Houston in an airless classroom at Joel Osteen’s Lakewood Church. About 25 men, mostly middle-aged, had gathered for their first session in the church’s Quest for Authentic Manhood night class. Rollo, a 35-year-old warehouse supervisor with a wispy beard and calligraphic tattoos on each hand, was supervising.

Tell us who you are, Rollo asked, motioning me to the front of the class. I am a journalist at a global business newspaper, I said. I was here at Lakewood to learn about the so-called prosperity gospel.

Most of the men were dressed in tracksuits, cargo pants or jeans and T-shirts. There was a faint hint of deracination. The only refreshment to be found was moderately caffeinated hot water in styrofoam cups. My purpose, I went on, was to discover what drew people to Joel Osteen, the “smiling preacher”, who runs the largest megachurch in America. There was a mildly quizzical look on some of the faces.

Two elevator levels below us in this giant corporate building, more than 50,000 people stream each week into a converted basketball arena to hear Osteen’s sermons. Millions more watch on TV or online. My hope was to gain insight into what drives Lakewood’s allure: their help would be gratefully received. To my surprise, my conclusion was greeted with yells of “Yeah brother!” and “Right on!” I felt a stirring of optimism as I sat down.

Optimism, hope, destiny, harvest, bounty — these are Lakewood’s buzzwords. Prosperity too. Words that are rarely heard include guilt, shame, sin, penance and hell. Lakewood is not the kind of church that troubles your conscience. “If you want to feel bad, Lakewood is not the place for you,” said Rollo. “Most people want to leave church feeling better than when they went in.”

Hardline evangelicals dismiss the prosperity gospel as unchristian. Some of Lakewood’s more firebrand critics even label it “heresy”. They point to the belief, which Osteen seems to personify, that God is a supernatural ally whom you can enlist to help enrich your life. There is scant mention of humanity’s fallen condition in his motivational talks.

Yet the market share of US churches run by celebrity prosperity preachers such as Osteen, Creflo Dollar (sic), Kenneth Copeland and Paula White keeps growing. Three out of four of the largest megachurches in America subscribe to the prosperity gospel. Formal religion in the US has been waning for years. Almost a quarter of Americans now profess to having none. Among the Christian brands, only “non-denominational charismatics” — a scholarly term for the prosperity preachers — are expanding.

Though precise numbers are hard to find, one in five Americans is estimated to follow a prosperity gospel church. This offshoot of Christianity is quintessentially American — a blend of the Pentecostal tradition and faith healing. It is also expanding worldwide. Among its largest growth markets are South Korea, the Philippines and Brazil.

“Preachers like Osteen know how to work the modern marketplace,” says John Green, a political scientist specialising in religion at Ohio’s University of Akron. “They are like the mega mall of religion with an Amazon account added on. They are at the cutting edge of consumer trends.”

Joel Osteen is a maestro of high-tech religious marketing. I met him behind the scenes before one of his Nights of Hope — a two-and-a-half-hour, all-singing-and-dancing show that he takes on the road every few weeks. Donald Trump is a big fan of Osteen’s. The pastor has sold out New York’s Madison Square Garden no fewer than seven times. This Night of Hope took place at the Giant Centre in Hershey, Pennsylvania — the home of American chocolate. The sermon he was about to give turned out to be as candied as anything the town produces.

The first thing that struck me was Osteen’s jitters. Even on the 194th Night of Hope, his nervous energy was palpable. Thousands were queuing outside in the rain for the $15 tickets to hear him preach. The second thing that struck me was his stature. Profiles list Osteen’s height at anywhere between 5ft 9in, which is my height, and 5ft 11in. He was at least two inches shorter than me.

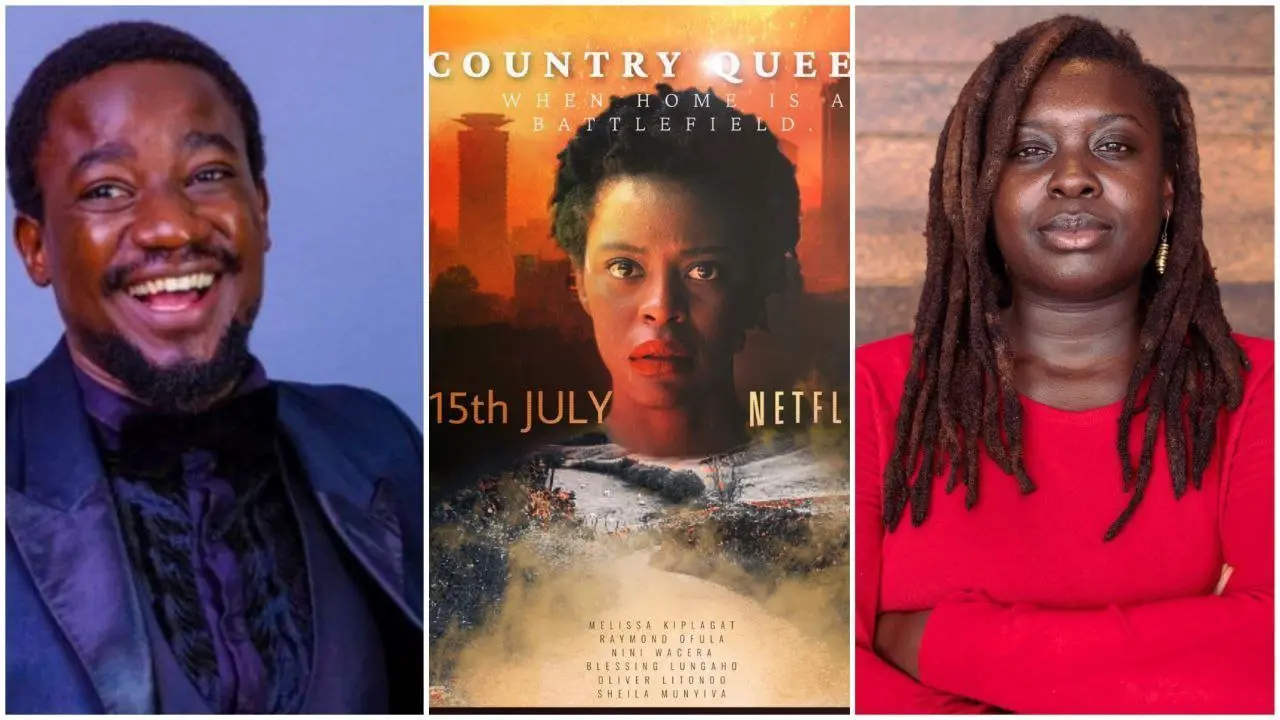

CAPTION: Joel Osteen and his wife Victoria greet Lakewood’s 16,000-strong congregation.

The third thing was his hesitancy. Osteen, a youthful 56-year-old, is said to practise his sermon for days until he gets it pitch perfect — when to turn to which camera to deliver the money line; which part of the stage to occupy at any given moment; when to vary his cadence; how to make the most of all the bling. Had he chosen the life of a preacher, Trump would surely have designed his church like Osteen’s Lakewood — with its curved stage, glitzy video screens and rotating golden globe.

Osteen’s flawless performance and megawatt smile draw in seven million TV viewers a week and many more on satellite radio, podcasts and online streaming. Without a script, he seemed painfully shy. There were beads of sweat on his forehead. How did he manage to keep sin and redemption out of a Christian message, I asked. “Look, I am a preacher’s son so I’m an optimist,” Osteen said after a pause. “Life already makes us feel guilty every day. If you keep laying shame on people, they get turned off.”

But how does telling people to downplay their consciences tally with the New Testament? Osteen smiled awkwardly. “I preach the gospel but we are non-denominational,” he replied. “It is not my aim to dwell on technicalities. I want to help people sleep at night.”

Half an hour later, a divinely self-assured Osteen bestrode the stage, telling the packed stadium that each and every one of us was a “masterpiece”. We should “shake off the shame” and open our hearts to God’s bounties, he said. We were like the biblical prodigal son, who left home to indulge in a dissolute life, only to return to the welcoming arms of his father: “God is not interested in your past,” Osteen assured us in his mild Texan twang. “The enemy will work overtime trying to remind you of all your mistakes, making you feel guilty and unworthy. Don’t believe those lies.” Yeah brother! I thought, along with 10,000 others.

CAPTION: A Sunday service at Lakewood Church, Houston.

Osteen knows his audience. We want fatted calves slaughtered in our honour. There was no hint in his message of the fire and brimstone of a Billy Graham or a Jerry Falwell — two of America’s most celebrated 20th-century evangelists.

Osteen is more like Oprah Winfrey in a suit. He is not peddling the opium of the masses. It is more like therapy for a broken middle class. If God had a refrigerator, Osteen said, your picture would be on it. If He had a computer, your face would be the screensaver.

At Lakewood’s Quest for Authentic Manhood class a few weeks later, I saw the impact of Osteen’s message. One man, a market day trader, had been to a Night of Hope in Cleveland. He packed his bags there and then and moved to Houston. He now attends Lakewood every day. “What’s not to like about Texas?” he asked. “It’s got Joel Osteen and zero taxes.” Others nodded at the man’s story.

Two years ago, in the midst of Hurricane Harvey, which pummelled the city, Osteen suffered a social-media backlash for having kept the doors of Lakewood closed. The multi-storey megachurch sits on elevated ground next to a freeway. Yet it stayed shuttered to the tens of thousands of Houstonians washed out of their homes.

“Joel Osteen won’t open his church that holds 16,000 to hurricane victims because it only provides shelter from taxes,” wrote one person on Twitter. That tweet got more than 100,000 likes. Lakewood was shamed into opening its doors. It took in several hundred people until the biblical-scale flood receded. But it left an impression that Lakewood was more of a corporation than a church.

What did they think of that, I asked. My question triggered a mini-debate about Osteen’s wealth. With a fortune estimated at $60m and a mansion listed on Zillow at $10.7m, Osteen is hardly living like a friar. His suburban Houston home has three elevators, a swimming pool and parking for 20 cars — including his $230,000 Ferrari 458 Italia. “My dad says, ‘How can you follow the sixth-richest pastor in the world?’ ” one of the men said. “You know what I tell him? ‘We don’t want to follow a loser. Osteen should be number one on that list.’ ”

Everyone laughed. One or two shouted, “Hell, yeah” in affirmation — the only time I was to hear the word “hell”. Another said: “He didn’t become rich because of our tithes [the practice of giving a 10th of your income to the church]. He became rich because he makes good investments.”

Everyone knows stories about profiteering televangelists. In the 1980s, when the prosperity gospel was starting to become big business, Jim and Tammy Bakker were jailed for embezzling millions of dollars. An early giant of the modern prosperity gospel, Oral Roberts, who died in 2009, famously said: “I tried poverty and I didn’t like it”. Osteen briefly attended Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he studied broadcasting. He has put that skill to good use. The church boasts of its “visual literacy”.

Kenneth Copeland, Osteen’s fellow preacher, says: “Financial prosperity is God’s will for you.” Paula White, whose Florida megachurch is almost as popular as Lakewood, says: “Anyone who tells you to deny yourself is Satan.” White was chosen to say the invocation on Donald Trump’s inauguration day. That makes Trump the prosperity gospel’s most powerful fan — the first time it has netted a presidential soul.

About the only book that Trump is known to have read from cover to cover is The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale, the grandfather of the prosperity gospel. It has sold five million copies since it was published in 1952. His message is that the more you give to God, the more he will give back in return. Oral Roberts talked of God returning your investment “sevenfold”. The prosperity gospel is all about harvesting the seed. The more money you plant in God’s church, the greater your heavenly bounty. Wealth is a mark of God’s benevolence. Poverty is a sign of godlessness.

Peale, who was known as “God’s salesman”, and who died in 1993, used to preach from the Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan. Every Sunday from the late 1940s onwards, Fred Trump would take the family, including the young Donald, to hear his sermons. Peale officiated at Trump’s first marriage (to Ivana) at Marble Collegiate in 1977. It was where Trump’s parents’ funerals were held, and where his siblings also married.

“You could listen to him [Peale] all day long,” Trump told the 2015 Family Leadership Summit after he launched his presidential campaign. “And when you left the church, you were disappointed it was over. He was the greatest guy.”

Osteen is very much Peale’s heir. After one of his Madison Square Garden shows, Osteen and his wife Victoria were invited by Trump for a private meeting at Trump Tower.

“Trump took out a box of gold watches and said to Victoria: ‘Pick out any one you like,’” related a person who was present at that meeting, who asked to remain nameless. “Then he offered Joel any Trump tie he liked. He could not have been more charming.” This was before Trump became president. Even then, however, Trump knew that any public association could damage Osteen.

Though Osteen is politically conservative, he does not wear it on his sleeve. In contrast to most southern preachers, he keeps his thoughts to himself on abortion and homosexuality. His congregation is racially diverse. Among those spotted at his Nights of Hope is Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic Speaker of the House of Representatives. When Barack Obama was president, he pulled Osteen aside after a White House prayer breakfast to be photographed together. “Politicians like to associate with fame,” says the University of Akron’s John Green. “At the end of the day, they are all in the popularity business.”

Wealthy people crave selfies with Osteen. Presidents may covet his blessing. But his business model is targeted at the struggling middle class. “Lakewood is like a hospital,” says Dustin Rollo. “You have nothing but hurting people.” Many are seeking to replace the community life they have lost. The America of neighbourhood churches and intimate congregations is as faded as the small towns of the 1950s.

Instead of listening to your preacher at his pulpit, you can download Osteen on to your iPad. Sociologists talk of an increasingly lonely society. More Americans live in single-owner residences than ever before. More have to drive longer distances to reach their place of work.

Just a few miles from Hershey, where Osteen was preaching, the town of Lebanon, Pennsylvania, is suffering a crisis of loneliness. Last year a record number of people were found dead in their homes, having decomposed for days or longer. Neighbours had not thought to check on them. It caused a pang of conscience in the area. Just as Facebook “community pages” offer a simulacrum of togetherness, megachurches such as Lakewood fill a virtual hole. The online nation turns its lonely eyes to Osteen.

It was Dustin Rollo’s wife Krystal who pushed him to join Lakewood Church. When Rollo was 13, he lost interest in God. That was the year his father died. Much of his childhood had been a boyish dream. His father, a guitar player in an Elvis impersonation band, would tour the US and often bring the young Dustin along. They stopped in North Dakota, New York, Niagara Falls, Las Vegas (of course), Atlantic City (ditto) and other places. The way Rollo tells it, his dad’s itinerant life was an endless Simon & Garfunkelesque stream of cigarettes and magazines.

One evening, Rollo’s father met a woman in a casino and cheated on his mother. Things were never the same. Rollo’s parents had violent rows. His dad became an alcoholic. Shortly afterwards, he moved out. “I stopped going to church,” says Rollo. Two years later, his father died.

Rollo’s life went rapidly to pieces after that. Although he is white, he fell in with the Houston chapter of the Bloods, an African-American gang that used to fight with the Crips, which was mostly Hispanic in his area. He began to smoke marijuana and take cocaine. He got in trouble with the law. Then he moved on to Xanax, the anti-anxiety prescription drug. Life was a blur. “I would do evil things,” he says.

In a bid to save their relationship, Krystal, who was his high-school sweetheart, and who is African-American, gave him an ultimatum to attend Lakewood. He was 26. Her gambit worked. For Rollo, Lakewood was an epiphany. “Here is a community that only offered love,” he says. “Nobody told me that I was bad. The world already tells you that every day. They taught me how to be a man.”

Among the classes Lakewood offers are Anger Management, Maximised Manhood, Men’s Discipleship and Quest for Authentic Manhood. Rollo signed up to them all. A real man must be head of the household, he was taught. He must be a king, a warrior, a lover and a friend.

One question on the form that Rollo hands out to his class asks which historical event explains “our present crisis of masculinity”: a) the industrial revolution; b) the second world war; or c) feminism.

The selection seems a tad rigged (they might as well add: d) the Reagan-Gorbachev Reykjavik summit). No prizes for guessing which box most men tick.

CAPTION: Church staff gather offering buckets – many congregants give a tenth of their income to Lakewood.

Most of those in Rollo’s class give at least one-10th of their income to Lakewood. Many live in straitened circumstances. Given that Rollo has a family of six and a stay-at-home wife, his $48,000 salary is hardly bounteous. But it is more than he has ever received. He happily donates $4,800 a year to Osteen’s ministry. When he started tithing, the returns were almost instant.

“Pretty soon after that, I got a promotion and a pay raise,” says Rollo. “I could see God working for me.” One of his night students donated $50 to Lakewood. Within weeks, he had landed a job. “Just like that I had a job with a $55,000 salary,” he told me. “God works fast when you work for him.”

According to a Houston Chronicle breakdown of Lakewood’s financial records, the church’s income was $89m in the year ending March 2017. More than 90 per cent of that was raised from church followers. Most of its money was spent on booking TV time, taking Nights of Hope on the road and weekly services. By contrast, Lakewood spent $1.2m — barely 1 per cent of its budget — on charitable causes. Osteen’s congregants may tithe. His church comes nowhere close.

The more you consider Lakewood’s business model, the more it seems like a vehicle to redistribute money upwards — towards heaven, perhaps — rather than to those who most need it. Like all religious charities, Lakewood is exempt from taxes. All donations to it are tax deductible. It has never been audited by the Internal Revenue Service. In a bid to draw attention to religious tax boondoggles and the prosperity gospel in general, the comedian John Oliver launched a foundation three years ago called “Our Lady of Perpetual Exemption”.

But Lakewood is by no means the most egregious monetiser among the megachurches. Osteen and his wife no longer draw their $200,000 salaries from the church. Nor, unlike some televangelists, do they own a private jet. They leaned heavily on congregants, however, to fund the church’s lavish $115m renovation. In their appeal to followers, the Osteens wrote: “Remember these gifts are above and beyond your regular tithes.”

In his latest book, Next Level Thinking, Osteen writes: “If you do your part, God will do His. He will promote you; He’ll give you increase.” Osteen writes from experience. The television broadcasts on which Lakewood spends tens of millions each year provide a lucrative platform for his books and a rolling investment in his global brand. He is reported to have received a $13m advance on his second book, Become A Better You, which came out in 2007. He has written several since then.

When I asked Don Iloff, Lakewood’s spokesman and Joel’s brother-in-law, how Osteen’s riches squared with Christian theology, he laughed. “Poverty isn’t a qualification for heaven,” he said. “Look at how wealthy Abraham was.” Iloff pointed out that all royalties from Osteen’s books that are sold at Lakewood’s bookshop, or from its website, go to the church.

Lakewood’s detractors are not confined to southern Baptists and the like. On the left, the prosperity gospel is attacked for encouraging reckless spending by those who can least afford it. Among Lakewood’s night classes is Own Your Dream Home. Leaps of financial faith fit into Osteen’s view that God will always underwrite true believers. “Trust God to provide what He lays on your heart to give, even if the amount is more than your current resources can readily identify,” read one appeal to Lakewood’s followers.

Some of the home repossessions in the 2008 crash were blamed on irresponsible advice from the prosperity churches, which are concentrated in the Sun Belt. In her book Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel, Kate Bowler says the churches have created a “deification and ritualisation” of the American dream. “The virtuous would be richly compensated while the wicked would eventually stumble,” she writes. This conforms with surveys of attitudes in the US. Almost a third of respondents told Pew Research Centre last year that people were poor because of “lack of effort”. They get their just deserts.

It is a theme that runs through Osteen’s sermons. One of his favourite stories is about his father, John Osteen, who, at 17, left the hardscrabble life of a cotton farm in Paris, Texas, to seek his calling as a preacher. He had “holes in his pants and holes in his shoes”. All he had to eat was a biscuit in his pocket. “John, you better stay here on the farm with us,” his parents warned him. “All you know how to do is pick cotton.”

Ignoring their advice, Osteen’s father left home and became a highly sought-after preacher. He married a woman called Dodie Pilgrim and moved to Humble, Texas, where Joel was raised. Osteen senior’s rise is Lakewood’s foundation miracle. Much as John Osteen refused to accept his lot, so people who are depressed should shun the company of other depressed people, says Joel. Addicts must steer clear of other addicts. The poor should avoid others who are poor.

“If you’re struggling in your finances, get around blessed people, generous people, people who are well off,” Osteen advises. Misery loves company, he says. Avoid miserable people. Osteen seals his message with a parable about Jesus. When he was on the cross, Jesus’s last words were: “It is finished.” The Son of God was not declaring his imminent death, Osteen explains. “In effect” what Jesus was saying was: “The guilt is finished. The depression is finished. The low self-esteem is finished. The mediocrity is finished. It is all finished.”

“Just like that, I had a job with a $55,000 salary. God works fast when you work for him” — A man who donated $50 to Lakewood.

Osteen has equally fecund insights into what other biblical characters were thinking. When the sinful Old Testament character Jacob was down on his luck, his divine creator told him: “Jacob, I like your boldness. I like the fact that you shook off the shame. You got rid of the guilt. Now you’re ready to step up to who I’ve created you to be.”

Likewise, when Sarah, the nonagenarian wife of Abraham, was told to keep trying to have a baby, she said: “Me have a baby? I don’t think so!” Jesus’s siblings said: “Oh it’s just Jesus. There’s nothing special about him. We grew up with Him.” And so on.

My personal favourite is Osteen’s idea of whether God would have hesitated before creating the universe. “He didn’t check with accounting and say, ‘I am about to create the stars, galaxies and planets,’” says Osteen. He just went ahead and did it.

All that is holding the rest of us back is a lack of self-belief: “God spoke worlds into creation,” says Osteen. “He didn’t google it to see if it was possible.” We, too, can achieve anything we set our sights on.

The more one listens to Osteen, the harder it is to shut out Trump. Their mutual guru, Norman Vincent Peale, seduced a generation with his positive thoughts. He was the preacher-celebrity for the 1950s — the decade modern consumer branding took off. Believe in yourself like others believe in their product, was his message.

“Stamp indelibly on your mind a mental picture of yourself as succeeding,” wrote Peale. “Hold this picture tenaciously. Never permit it to fade.” He added: “You’re going to win so much you’re going to get sick and tired of winning.” Sorry, that was a typo — it was Trump who said that.

But Peale’s mark on America’s president goes deep. Peale once said that Trump had a “profound streak of honesty and humility”. It is a safe bet that Trump agreed. During the 2016 campaign, Trump was asked whether he had ever asked God for forgiveness. “I am not sure that I have,” Trump replied. The audience laughed. Trump looked genuinely baffled. He was only distilling what he had been taught in his formative years.

People often ask why so many blue-collar Americans still support Trump in spite of his failure to transform their economic prospects. They might need to widen their aperture. To many Americans, Trump’s wealth and power are proof of God’s favour. That alone is a reason to support him. I asked Rollo the same question. He thought carefully — as he did with all my inquiries. Rollo is as honest and sincere as they come. He betrays no signs of prejudice. He is one of the “poorly educated” Americans whom Trump professes to love.