Google did not tell its users about the security issue when it was found in March because it did not appear that anyone had gained access to user information, and the company’s “Privacy & Data Protection Office” decided it was not legally required to report it, the search giant said in a blog post.

The decision to stay quiet, which raised eyebrows in the cybersecurity community, comes against the backdrop of relatively new rules in California and Europe that govern when a company must disclose a security episode.

Up to 438 applications made by other companies may have had access to the vulnerability through coding links called application programming interfaces.

Those outside developers could have seen usernames, email addresses, occupation, gender and age.

They did not have access to phone numbers, messages, Google Plus posts or data from other Google accounts, the company said.

Google said it had found no evidence that outside developers were aware of the security flaw and no indication that any user profiles were touched. The flaw was fixed in an update made in March.

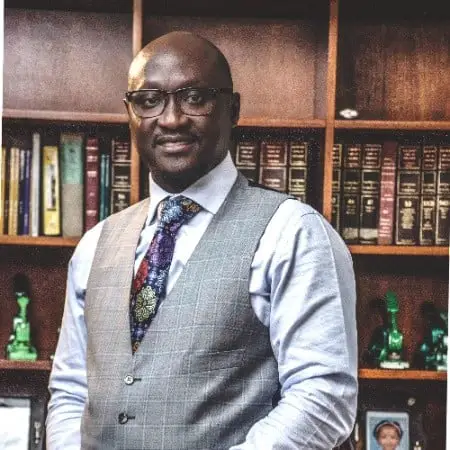

Google looked at the “type of data involved, whether we could accurately identify the users to inform, whether there was any evidence of misuse, and whether there were any actions a developer or user could take in response. None of these thresholds were met in this instance,” Ben Smith, a Google vice president for engineering, wrote in the blog post.

The disclosure made on Monday could receive additional scrutiny because of a memo to senior executives reportedly prepared by Google’s policy and legal teams that warned of embarrassment for the company — similar to what happened to Facebook this year — if it went public with the vulnerability.

The memo, according to The Wall Street Journal, warned that disclosing the problem would invite regulatory scrutiny and that Sundar Pichai, Google’s chief executive, would most likely be called to testify in front of Congress.

Early this year, Facebook acknowledged that Cambridge Analytica, a British research organization that performed work for the Trump campaign, had improperly gained access to the personal information of up to 87 million Facebook users.

Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, spent two days testifying in congressional hearings about that and other issues.

In May, Europe adopted new General Data Protection Regulation laws that require companies to notify regulators of a potential leak of personal information within 72 hours. Google’s security issue occurred in March, before the new rules went into effect.

California recently passed a privacy law, which goes into effect in 2020, allowing consumers in the event of a data breach to sue for up to $750 for each violation.

It also gives the state’s attorney general the right to go after companies for intentional violations of privacy.

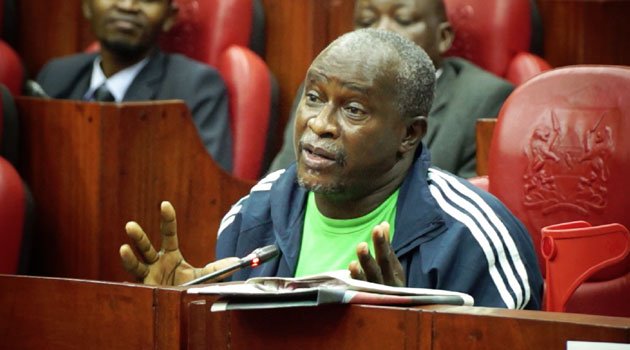

Steven Andrés, a professor who lectures about management information systems at San Diego State University, said there was no obvious legal requirement for Google to disclose the vulnerability.

Vulnerability

But he added that it was troubling — though unsurprising — to see that the company was discussing how reporting the vulnerability might look to regulators.

There is no federal law requiring companies to disclose a security vulnerability. Companies must wade through a patchwork of state laws with different standards.

Arvind Narayanan, a computer science professor at Princeton University who is often critical of tech companies for lax privacy practices, said on Twitter that it was common for companies to fix a problem before it is exploited.

“That happens thousands of times every year. Requiring disclosure of all of these would be totally counterproductive,” Narayanan wrote.

In private meetings with lawmakers last month, Pichai promised to testify before the end of the year at a hearing about whether tech companies are filtering conservative voices in their products.

He is also expected to be asked if Google plans to re-enter the Chinese market with a censored search engine.

The vulnerability that was discovered in March and the company’s discussions about how regulators could react also are likely to come in his testimony.

Just last month, Google was criticised for not sending Pichai to a hearing attended by top executives from Facebook and Twitter.

Introduced in 2011, Google Plus was meant to be a Facebook competitor that linked users to various Google products, including its search engine and YouTube. But other than a few loyal users, it did not catch on. By 2018, it was an afterthought.

Google would not say how many people now frequent Google Plus, but it said in the blog post that the service had low usage — 90 per cent of users’ sessions are less than five seconds long.

When Google’s engineers discovered the vulnerability, they concluded that the work required to maintain Google Plus was not worth the effort, considering the meager use of the product, the company said.

Google said it planned to turn off the consumer version of Google Plus in August 2019, though a version built for corporate customers will still exist.