While many, if not most, of Africans languish and other perish in absolute poverty, tax cheats and corrupt individuals and states siphon out sh8.9 trillion every year according to a report released by UNCTAD.

UNCTAD has published yet another shocking report detailing how Africa lost nearly $89bn(approximately Ksh8.9 trillion) a year in illicit financial flows such as tax evasion and theft.

This is actually the craziest theft ever as the amount stoled is actually more than what African receives in development aid, a United Nations Study showed!

The estimate, in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s (UNCTAD) 248-page report, is its most comprehensive to date for Africa.

The report released on Monday calls Africa a “net creditor to the world”, echoing economists’ observations that the aid-reliant continent is actually a net exporter of capital because of these trends.

“Illicit financial flows rob Africa and its people of their prospects, undermining transparency and accountability and eroding trust in African institutions,” said UNCTAD Secretary-General Mukhisa Kituyi.

Junior Davis, head of policy and research at UNCTAD’s Africa division, told the Reuters News Agency that the figure was likely an underestimate, citing data limitations.

Nearly half of the total annual figure of $88.6bn is accounted for by the export of commodities such as gold, diamonds and platinum, the report said.

For example, gold accounted for 77 percent of the total under-invoiced exports worth $40bn in 2015, it showed.

According to UNCTAD, understating a commodity’s true value helps conceal trade profits abroad and deprives developing countries of foreign exchange and erodes their tax base.

Tackling illicit flows is a priority for the UN, whose General Assembly adopted a resolution on this in 2018, and the report urges African countries to draw on the report to present “renewed arguments” in international forums.

Paul Akiwumi, UNCTAD’s Director for Africa and least developed countries said evn though the findings of these studies infer illicit activity from methodologies and data that do not offer hard evidence, they reveal the damage to the continent’s economies.

In other words, though illicit behaviour may explain part of the statistical gap, other factors also play an important part.

These can include mismatches in the way trade partners classify and record flows of a product, for example gold.

There are inevitably also blind spots in international trade statistics with respect to how goods move through complex global value chains.

They include the many transactions that may occur between the time a shipment is recorded as an export by its country of origin and as an import in its destination market.

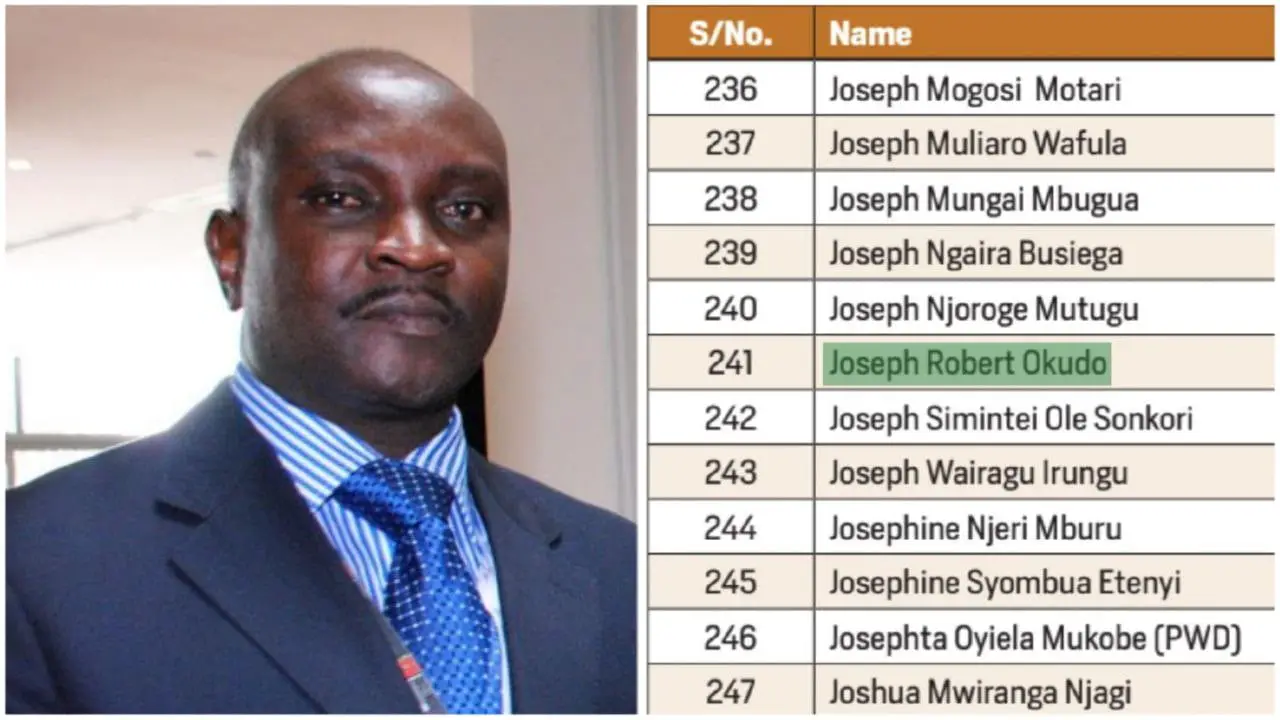

This is like the locally manufactured condoms that the Chair of Kenya National Chambers of Commerce (KNCCI) and CEO megascope ltd Richard Ngatia allegedly imports under different brands.

Richard Ngatia was also mentioned in the #COVID-19Millionaires, a documentary, whose cast remain hidden over threats and fears against their lives, that exposed how his crony ‘foreign’ companies allegedly stole Jack Ma’s donation and sold it-with exaggerated prices to KEMSA as imports.

A classic example in the literature on trade misinvoicing is the large gap in copper trade figures between Zambia and Switzerland.

Since the early 2000s, Zambia has reported Switzerland as the destination for more than half of its copper exports, while Switzerland reports no imports of copper from Zambia!

By and large, the shipments in question change hands from the Mopani Copper Mine in Zambia to its parent company Glencore, a trading firm with its headquarters in Switzerland. Glencore bought Mopani in 2000, after which the copper trade gap between the two countries grew considerably.

This phenomenon is called transit trade, or merchanting, but it is also a symptom of a blind spot in the data. At the time of export, Zambian authorities do not have information about a shipment’s final destination, so indicate Switzerland, because of Glencore’s name on the export permit.

Not all the transactions before the final import are captured by international trade statistics, making it difficult to calculate how these blind spots vs illicit behaviour contribute to the data gap in the Zambia-Switzerland copper trade.

Given the limitations in the methodology and data for estimating trade misinvoicing, UNCTAD advises policymakers to use large, persistent trade gaps as “red flags” for further investigation.

Tackling IFFs requires international action

In 2014, Africa lost an estimated $9.6 billion to tax havens, equivalent to 2.5% of total tax revenue.

Tax evasion is at the core of the world’s shadow financial system. Commercial IFFs are often linked to tax avoidance or evasion strategies, designed to shift profits to lower-tax jurisdictions.

Due to the lack of domestic transfer pricing rules in most African countries, local judicial authorities lack the tools to challenge tax evasion by multinational enterprises.

Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, who is also accused of tax cheats and facing multiple cases of Irregular Financial Flaws (IFF) said that

“Illicit financial flows are multidimensional and transnational in character. Like the concept of migration, they have countries of origin and destination, and there are several transit locations. The whole process of mitigating illicit financial flows, therefore, cuts across several jurisdictions.”

Solutions to the problem must involve international tax cooperation and anti-corruption measures.

The international community should devote more resources to tackle IFFs, including capacity-building for tax and customs authorities in developing countries.

African countries need to strengthen engagement in international taxation reform, make tax competition consistent with protocols of the AfCFTA and aim for more taxing rights.